Vizenchaft was a profound child. Raised to love truth and justice, and he did, for a while. The elves said afterward, “He was too much of us.” And the trees agreed.

He talked little, but observed much. He sometimes had this manner about him of almost severe curiosity. At the song-dance he was always watching and sometimes writing little notes. These early writings were later found to contain marvelous mathematical discoveries on the nature of the celebration’s intricacies. Limb and note moved with contra-logarithmic precision and knowledge of one could predict the other. The mystics ponder this strange beauty still and cannot unlock its true meaning, and neither could he. But his genius saw the patterns first.

He devoted himself to the study of the world: the growing of the fields, the workings of society, the making of carts and shields, the navigating of the ships. He listened to what all had to say and gathered knowledge from every mind. He was intelligent yes, but also compassionate and introspective. He was made a High Judge. It seemed that he could hardly imagine making an unjust or unmeasured ruling. Often he could be heard remarking, “What can we do but learn what is true and live what is true?”

Of course, he fell in love. His wife was Leben. He was her delight, and she was his strength. She would ask him all sorts of questions just for the pleasure of hearing him answer with wisdom and understanding. And when Vizen saw cruelty or foolishness, it was difficult for him. He could not understand why people would act the way they did, and it pained him. Yet it did not hurt Leben the way it hurt him. Her love seemed to go behind and beyond the wrongs of the world. Hers continued where his might get confused.

Soon, they had a daughter named Fryda. Mother and father would sing softly to her every night until she feel asleep, at peace. And never was there an infant who laughed more! The whole town brightened when young Fryda gave her happy giggle.

But Fryda’s laughter was broken. The small family developed feverish cough, and were committed to a fortnight’s quarantine. When the doors were opened, only he remained. The mother and daughter had died on the eleventh day.

Vizenchaft’s body recovered. But bodily wounds are often not deepest.

He gave them back to the trees, and we are grateful for that. He lived apart for a time. Some who loved him went to him, sometimes weeping, sometimes speaking grief, sometimes just sitting. It was noticed however, that he did not weep, and he did not speak grief. Indeed, he barely spoke of what had happened at all.

At length, golden-hearted Neben said to him, “Friend, you know that those years ago, when my child died, you told me that it was good to weep, and you told me that it was good to speak grief. Now I tell you the same. You are free here to shed tears and cry out, and I tell you it is good to do so.”

But the change was first seen in him when Vizen responded, “Why? Why is it good to weep? I told you it was good then, but now I tell you this. Weeping will not return the dead to the living. And speaking grief will not remove sickness from this world. No, not today will I do these things.” And Neben left him, dismayed.

Vizencraft returned to his Justly duties, but his court was changed. Less of mercy and more of philosophy was found there. Those accused would suffer long lines of questioning. Why did you choose to steal? Was there a time you thought you would never do this thing? How could you bear to lie; does it not hurt your soul? Why would you choose cruelty? And perhaps most common: Do you know that you will someday die? And he started to be seen nodding to their answers, when the answers were honest.

Neben and others continued speaking with him, but his questions for them were even more alarming:

Listen, why ought we be friends? Why not be alone? This is a safer way to live after all. It is unwise to indiscriminately be friends, is it not? And why is that? Because not everyone is worthy of trust, and trusting the untrustworthy with friendship can bring harm to oneself. But how can we know who is really trustworthy? Perhaps you are not, or perhaps I am not. Are any of us truly trustworthy?

What can we know of the world after this? Surely we can only know what has been told to us, and surely this is possibly a falsehood? Of course I do not suggest it is a falsehood, but merely that it could be. And this really could be for a variety of reasons. The Ones Across would not deceive us, but it has been many centuries since they sent someone to us, and is it not possible that those who have heard from them were mistaken? Or that we have merely forgotten the true words that were said? Surely we agree that even elves often forget. I have observed this many times. Then do we know what will happen when we die? And if not, what does this mean?

Why do you care for your wife? You say because you love her. This means that you are made happy when she is happy. So is it not the case that you care for your wife only to increase your own pleasure? Tell me, if she died, would you grieve that you lost your source of happiness, or would you be glad that she is in the next world? Is this something that should not be asked? Why is that? What questions should not be asked, and why should they not be asked?

Why is it that the weak deserve more care than the strong? Is it not the strong that build up? Is it not the strong that plow the fields? Should we not honor the strong above the weak? They have given much to us, while the weak have not given us anything. Furthermore, it is a common saying that “The strong have often felt great pain.” Does this not mean that removing pain from the weak is an injustice, in that it eternally keeps them weak?

And many more such questions did he ask.

Vizencraft continued like this for some time. But suddenly, he announced, “My learning is not complete,” and ceased speaking with anyone. He resigned his court. He could be found walking for many hours of the day, or dealing with strange creatures near the cliffs or harbors. He acquired nearly forgotten texts and learned ancient tongues.

He had always shown a distrust of magic, as elves often do, even now. But during this time he was first seen learning small sorceries, for making things invisible, or creating hot ice, or changing the sizes or shapes of things.

The shopkeepers quarreled with him. His appearance had become less stately and groomed, and had rapidly descended into something scarcely seen in elven culture. “Does this change who I am?” He would say. But the clerks did not approve of this, and wished him out of their stores. One day he decided to be mischievous. The most valuable items in each of the main stores would suddenly disappear, only to reappear later, doubled in size.

Increasingly he was rejected by those around him. And increasingly he would laugh at them. To the women he shouted “fat.” To the warriors he shouted “coward.” To the husbands he shouted “slave.” To the beggars he shouted “worthless.” To the teachers he shouted “idiot.” To the children he shouted “leech.” To the rulers he shouted “liar.” And to all he shouted “fool.”

Vizencraft knew in his heart what he wanted to do. At the harbors he had learned that the cure for the illness that took the life of his wife and daughter was broadly known and simple to administer. But the healer in his town, while skilled, happened to be ignorant of this particular remedy.

His rationality cried out that the healer could not be blamed, and that she had done all that she could. And yet, ever since learning of the cure, he had desired revenge. He discovered that he had an unconquerable desire to subject the healer to anguish and death, as his wife and daughter had been subjected.

He knew that this would not truly give him pleasure, and yet still he desired it, and this was his dilemma. He had organized his life around the belief that pleasure was the purpose of life, but found no way towards pleasure. It seemed a contradiction. He concluded that this was, in fact, just how he worked. His nature was arranged to be simply unable to feel pleasure when put in this scenario—and the moment he considered this, his soul was shattered. He discovered that he no longer cared about what was right or true, and nothing could change the singular desire to do an irrational murder. And so he hated his nature. In his journals he wrote, “I am an abomination.” And later, he called all thinking creatures the same. He hated consciousness and reason and life itself.

He began to think and to plan afresh. How could he resolve this hideous problem? If the pain comes from his root, how can he avoid it? Was there any possible way? This was the question he pondered again and again.

Slowly, a new idea formed. Could he go down deeper than even his own nature? Could he perhaps change his nature to take pleasure in a murder? If this is possible…. Maybe this is the solution.

And so he left his land to seek what is beyond the cliffs and the harbors. He met many mages and they taught him many things. He sucked the marrow out of bones and hid spiders under his skin. He built a flesh of blades and bathed in rotting mold. He hated birds the most, and slew many for their eyes.

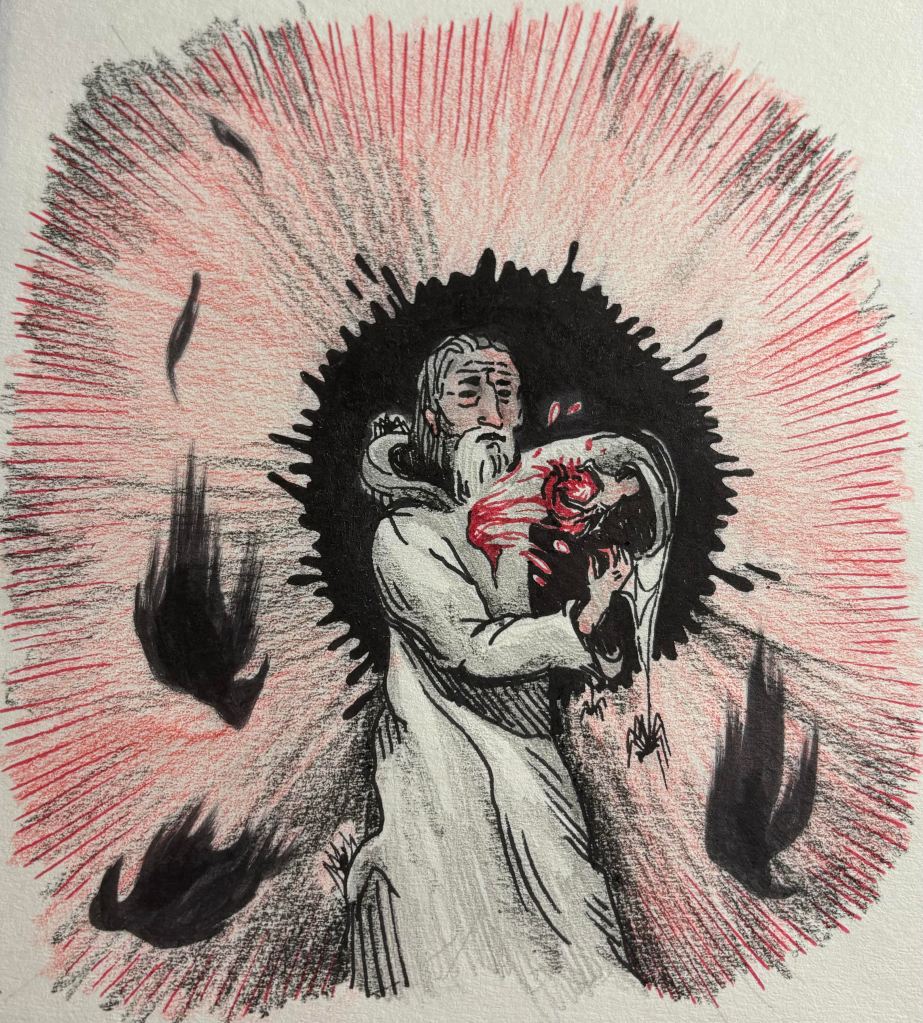

Finally, reeking and grotesque, he met one mage with a soulless stare. He asked this mage how he could become like him. The mage responded, “You must have no heart to be fully your will.” And Vizen understood. Even now, his nature screamed at him that this was not the way. He did not want to do it. But he had to be rid of this contradiction of desire. He reached into his chest, clutched his own heart, and ripped it from himself. He watched it fall to the ground. And he gained the soulless stare.

This accomplished, he now knew that nothing in his will could ever contradict itself again. He returned to find the innocent healer, and tormented her for days before moving her to the next world. And he felt pleasure in this. And indeed, he also felt pleasure that he felt pleasure.

But then, she was dead. The deed was over. His plan complete. And he didn’t know what to do next. He found that he had no desire to do anything further. He did not desire to rest, or eat, or blink, or breathe.

Someone found him there, surrounded by bits of a tortured corpse, and fled in terror.

Soon after, a group of soldiers rushed him, shouting out threats and disarming him violently. He found the sensation of pain that was inflicted upon him to be interesting for a time, but only briefly.

The soldiers brought him to a gallows and quickly issued a sentence of death. The executioner reported that he said to himself at the end, “I am certainly powerful enough to kill all of these men and women, and perhaps I should. A rational will desires itself to continue. But I don’t find this to be the case within myself.”

And the trapdoor opened, and his neck snapped.

And thus his story ended.